Nouriel Roubini today blogs his new paper which argues that the US housing recession is far from bottoming out. In truth, however, the paper is really just a longer-than-usual blog: it generally asserts at least as much as it argues, and is written more colloquially than formally. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

There are basically two parts to the paper, which attempts to try to work out how much longer the current housing recession will continue. The first takes a basically chartist approach, looking at previous housing recessions and assuming that the present one will be similar. The second takes more of a supply-and-demand approach.

The problem is that a chartist approach is never particularly convincing, and certainly not in this case, where the charts themselves seem to disprove any attempt to demonstrate that the housing market has remotely predictable cycles. And the supply-and-demand approach has two big problems: it doesn’t explain housing-market movements in the past, and it basically assumes its own conclusions.

It’s also worth noting that nowhere in the paper does Roubini talk about housing prices, as opposed to housing construction. His definition of a housing recession is nowhere made explicit, but seems to be based on housing starts, and is certainly not based on house prices. So even if he’s right about the future of the housing recession, that doesn’t necessarily mean that prices will go down.

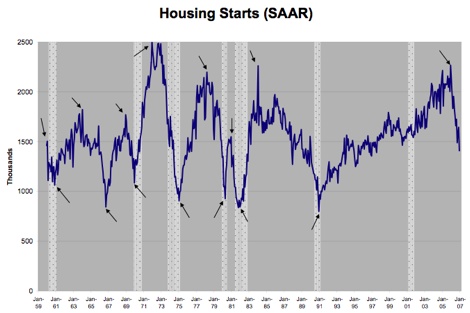

A few specifics, for those who care. First, his main chart:

A large amount of Roubini’s analysis comes from looking at this chart and performing all manner of inductive feats on it. He looks at the size of the drops between arrows, the amount of time elapsed between them, and so forth, and then makes predictions as to the position of the next up arrow based on those old datapoints.

This last housing recession lasted 12 months so far. The average duration of the previous seven housing recessions was 32 months. Housing starts are down (as of January 2007) 38 percent from the January 2006 peak, but only 16 percent from their moving average peak. In past housing recessions starts bottomed, on average, after a 51 percent drop form the peak, and after a 37 percent drop from the moving-average peak. Thus, the past housing recession episodes tell us that housing starts could fall another 13 percent from their actual peak (or another 21 percent from their moving average peak) and that it could take another 21 months to reach that bottom.

Is all this of any use to anybody? If you’d tried that technique with the last housing recession, which lasted 84 months by Roubini’s calculation, you’d have been well off base: the average of the previous six housing recessions was just 23.5 months. And you’d have been even more off base if you’d tried to predict the length of the last housing upturn, based on the length of previous housing upturns.

It does seem to me that Roubini is looking at an extremely noisy series and trying desperately to find patterns in that noise which simply don’t exist. I mean, just look at that chart. Does it really strike you as the kind of thing from which any useful prediction can be extracted? A nice pretty sine wave it is not.

Nevertheless, Roubini is so bought in to the concept of housing-market cycles that he writes things like this, without any empirical support:

Inventories are as important as excess inventories are crucial drivers of demand and supply cycles.

To be fair, I have no idea how one would even start trying to demonstrate that a given series was a “crucial driver” of any economic “cycle”. But whenever one reads a sentence like that, it’s worth remembering that it comes entirely from the world of economic theory, as opposed to the world of empirical fact.

After all the cycle-based stuff, it’s refreshing to get some real supply figures in the second half of the paper. After all, economic luddite though I am, I will concede that prices tend to go up when demand exceeds supply, and that they tend to go down when supply exceeds demand.

The problem is that although Roubini has supply figures dating back to 1968, he doesn’t really have any kind of data series at all on the demand side. So all of his calculations are based on demand increasing steadily with population growth: he makes no allowances, for instance, for shrinking family size. And although he’s happy projecting both supply and demand forward until 2010, he never stops to ask whether his model can explain the developments we’ve already seen in the housing market. After all, if the housing market hasn’t been following his rules of supply and demand for the past few decades, then there’s no particular reason it should start now. And all those crazy spikes in the housing-starts chart don’t look to me as though they were perfectly predictable reactions to changes in supply and demand. Or, to put it another way, the changes in supply and — especially — demand which caused those crazy spikes are hardly the kind of changes which Roubini is modelling in this paper.

It also seems to me that all of Roubini’s models assume what he’s purporting to conclude: that various data series, such as the stock of housing inventories, will revert to mean over the next four years. Again, this is chartism, and I see no reason at all to consider that assumption a reasonable one. And while Roubini’s predictions for supply in the housing market seem perfectly reasonable to me, I’m not at all convinced about his predictions with respect to demand. With prices stagnant and rents rising, it’s making increasing amounts of economic sense to buy rather than rent — and even to buy for rental income. Add to that the effects of mortgage-interest tax deductibility, and the effects of a weakening dollar on demand from overseas, and I think it’s quite easy to paint a scenario with rising, rather than falling, demand.

I should say that it’s entirely possible that Roubini is right, and that both housing starts and housing prices are going to fall substantially over the next couple of years. I certainly don’t have any privileged information on the subject. But he doesn’t either. And I’m no more convinced that the sky is falling now than I was before I read his paper.

The guys with the privileged information — housing executives — saying it’s going to “suck.” Who needs charts?

New housing starts have already dropped below the rate of household formation. What he’s counting on at this point is overshoot; I wouldn’t bet against overshoot in a financial market, but it does make the case for a continued pull-back a bit weaker on the fundamentals than the case for bearishness was a year ago.

The critical issue is housing “starts” only if there are no buyers and builders don’t notice.

It seems pretty healthy and an indicator of likely stability in housing prices/values if builders do something rational such as decrease production when they sense — and it is mostly “sensing” — a decreasing demand.

fs, why the cavil about prices? The significant datum for economic growth is indeed residential investment, for which starts are a fine proxy.

On rents, while real rents have indeed jumped in recent months, this follows years of declines in real terms. Deflate the CPI rent series by CPI ex-shelter. The average for 2006 was lower than for 2002. There are fine reasons to own, the very generous tax subsidy probably largest among the purely financial ones, but unless rents continue up further in real terms, their recent 3%-real bump likely changed almost nobody’s calculation.

dwj, on starts and household formation, please cite your source. I am curious what you have. One chart I made plots new sales per population change, viz http://www.bignose.org/~wcw/nhspopr.0612.png The data are noisy as heck (especially the Fed’s CNP16OV series I use for population), but the slow uptrend in the numbers that reflect increasing rates of household formation is pretty visible. Also visible is that either formation rates hit a new, high plateau in the early ’00s, or that it does not appear correct that housing starts have dropped below the rate of household formation.

I couldn’t read the full NR piece, but those for-sale-only vacancy numbers weigh in my mind. If starts have dropped below rates of formation, that is sustainable for some time until those empty units are filled.

I personally prefer the argument that housing will decline/stay flat (decline by inflation) by an eventual 20%+ in the major areas (EG, where I’m at in the SF bay area) by simply looking at the buy vs rent delta. Simply put, people have to live, but they don’t have to buy.

When they condo converted my apartment complex, interest, property tax, hoa, and maintinence, after the tax deductions in the “Bend over and take it like a man” 28% marginal tax bracket, would be $500/month more than rent. You have to assume a significant rate of continued appreciation PLUS a sale time 7+ years out in the future for it to have made sense to buy. Or some 3 year obscene teaser rate and the ability to flip 3 years out with continued greater-than-inflation appreciation.

(In contrast, whenever I ran the numbers for “rational” markets, eg in the midwest, or historical numbers from 2000 for a friend’s place in Virginia, Interest, property tax, + HOA/maintinence, after tax savings, is ~= to slightly less than rent).

Here in the SF bay area, prices haven’t collapsed, but the market has pretty much frozen: inventory is way up, prices are not going up, and starts are down. I’d expect this to continue slowly for the next few years, as prices are very sticky on the way down unless people HAVE to sell.

(The spreadsheet I made to do all the calculations is available by request, nweaver@gmail.com )

Why Seattle should be different I am not sure.

But we have had a great discrepancy between buying & renting since the early 1970s i.e. it has always been far more expensive to buy than to rent and very few (like show me one and I’ll buy it) residential properties ‘cash-flow’ at a 20% down purchase. But people do buy when they can afford it. As markets are not likely to be wrong over such a long period of time, my conclusion is that the psychological value of owning is simply worth the extra $$$ and responsibility.

So all you would-be owners hoping for a crash, it’s not likely if you live in the Seattle area.

David: In terms of raw cash flow, buying costs more than renting under ALL conditions I’ve looked at. Even in a “sane” market, on a cash-flow basis, buying is expensive.

But notice that for “cheaper then renting”, I only consider lost-money (interest, tax, HOA) as ‘cost’ for buying, the rest of that huge mortgage payment you should see again, evenutally, so I don’t consider that a cost.

I wonder if the size of residential housing is important.

I have witnessed that American homes have become almost palatial over the past 20/30 years, in accordance with the notion that if bigger is better then biggest is the best.

If lending gets tight, because of increases in interest rates, but unemployment does not falter badly, then might not people take out smaller mortgages to finance smaller houses?

Hey Felix, bet you’re feeling a little stoopid now, huh… 😀

Felix, aren’t you feeling a bit like a twit for writing this in March 2007.

Roubini turned out to be right. How about you guys write an article acknowledging his ways of thinking and that he was right.

do you want to be new one in the new year?sure of “yes”,so do not miss the top designers’ ,and promise that :the products have quality guarantee,free shipping,you can returnf it if unsatisfy.

do you want to be new one in the new year?sure of “yes”,so do not miss the top designers’ ,and promise that :the products have quality guarantee,free shipping,you can returnf it if unsatisfy.

Good page!

———————————————–

———————————————–