Meta

Categories

- accounting

- Announcements

- architecture

- art

- auctions

- bailouts

- banking

- bankruptcy

- ben stein watch

- blogonomics

- bonds and loans

- charts

- china

- cities

- climate change

- commercial property

- commodities

- consumers

- consumption

- corporatespeak

- credit ratings

- crime

- Culture

- Davos 2008

- Davos 2009

- defenestrations

- demographics

- derivatives

- design

- development

- drugs

- Econoblog

- economics

- education

- emerging markets

- employment

- energy

- entitlements

- eschatology

- euro

- facial hair

- fashion

- Film

- Finance

- fiscal and monetary policy

- food

- foreign exchange

- fraud

- gambling

- geopolitics

- governance

- healthcare

- hedge funds

- holidays

- housing

- humor

- Humour

- iceland

- IMF

- immigration

- infrastructure

- insurance

- intellectual property

- investing

- journalism

- labor

- language

- law

- leadership

- leaks

- M&A

- Media

- milken 2008

- Not economics

- pay

- personal finance

- philanthropy

- pirates

- Politics

- Portfolio

- prediction markets

- private banking

- private equity

- privatization

- productivity

- publishing

- race

- rants

- regulation

- remainders

- research

- Restaurants

- Rhian in Antarctica

- risk

- satire

- science

- shareholder activism

- sovereign debt

- sports

- statistics

- stocks

- taxes

- technocrats

- technology

- trade

- travel

- Uncategorized

- water

- wealth

- world bank

Archives

- March 2023

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- December 2012

- August 2012

- June 2012

- March 2012

- April 2011

- August 2010

- June 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- September 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

- June 2005

- May 2005

- April 2005

- March 2005

- February 2005

- January 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- October 2004

- September 2004

- August 2004

- July 2004

- June 2004

- May 2004

- April 2004

- March 2004

- February 2004

- January 2004

- December 2003

- November 2003

- October 2003

- September 2003

- August 2003

- July 2003

- June 2003

- May 2003

- April 2003

- March 2003

- February 2003

- January 2003

- December 2002

- November 2002

- October 2002

- September 2002

- August 2002

- July 2002

- June 2002

- May 2002

- March 2002

- February 2002

- January 2002

- December 2001

- November 2001

- October 2001

- September 2001

- August 2001

- July 2001

- June 2001

- May 2001

- April 2001

- March 2001

- February 2001

- January 2001

- December 2000

- September 2000

- July 2000

- March 2000

- July 1999

Not all winning bets are smart

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on Not all winning bets are smart

From Wall Street Dark Pools to Puerto Rican Swimming Pools

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on From Wall Street Dark Pools to Puerto Rican Swimming Pools

Aereo could have saved the airwaves from the broadcasters’ ransom

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on Aereo could have saved the airwaves from the broadcasters’ ransom

Hedge Fund vs. Sovereign

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on Hedge Fund vs. Sovereign

Why Argentina Could Default … Again

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on Why Argentina Could Default … Again

Spinoffs, Write-downs, and Techie Taxis

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on Spinoffs, Write-downs, and Techie Taxis

BuzzFeed’s Jonah Peretti Goes Long

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on BuzzFeed’s Jonah Peretti Goes Long

Lessons from a $110 million penthouse

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on Lessons from a $110 million penthouse

Wall Street’s Toughest Judge

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on Wall Street’s Toughest Judge

The number 2,000

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on The number 2,000

America prosecutes its interests and persecutes BNP

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on America prosecutes its interests and persecutes BNP

One question all managers should ask themselves about pay

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on One question all managers should ask themselves about pay

The economics of “everyone’s private driver”

Posted in Uncategorized

Comments Off on The economics of “everyone’s private driver”

Where is Felix

I left Reuters, and I’m not sure when or whether I’m going to have any kind of regular blog at Fusion. And in my new promiscuous life, it’s not going to be very easy to keep track of everything I’m doing. Which means that there’s now a job for felixsalmon.com to do! I’ll probably still post things here occasionally, but I’m also going to use this blog to link to everything else I’m doing at other places. Which has the benefit that this blog’s RSS feed will also serve as an RSS feed for everything I’m doing.

So! In recent weeks, I’ve written these pieces:

- Why I’m joining Fusion

- False equivalency in the NYT: How Jeremy Peters’s voter ID reporting is even more wrong than you think

- Why Salaries Shouldn’t Be Secret, a post which was extremely popular on LinkedIn

- Tim Geithner, unreliable narrator: You can’t trust what you read in his book

- How CitiBike is like Ecuador: What’s the point of having a contract, if there’s no remedy?

I’ve also started my weekly podcast for Slate. So far there have been four episodes:

- The Debut of Slate Money: On the upcoming IPO of Chinese Web giant Alibaba, the battle between Sotheby’s auction house and its Dan Loeb, and Seattle’s possible move to a $15 minimum wage.

- The Unbearable Modesty of Tim Geithner: On Tim Geithner’s Stress Test, why Christine Lagarde isn’t speaking at Smith College, and how student debt impacts the housing market.

- Ben Bernanke’s Big Payday: On Credit Suisse’s guilty plea, how reparations to descendants of slaves might work, and whether it’s appropriate for former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke to accept six-figure speaking fees.

- Money and the Media: On Apple’s purchase of Beats, Amazon’s fight with Hachette, and Thomas Piketty’s defense of his data.

Do subscribe to the podcast directly, if you’re into such things, and leave a rating on iTunes. It’s a great way to help people discover it. Thanks!

Posted in Uncategorized

1 Comment

Scoops: When journalists masturbate

“Breaking news is the most masturbating thing journalists do” – @felixsalmon, Fusion #ijf14 pic.twitter.com/Pu5elT6XRz

— journalism festival (@journalismfest) April 30, 2014

This quote is beginning to get some press attention, so I ought to correct the record: I said “masturbatory”, not “masturbating”. Glad that’s cleared up.

In fact, the full quote was captured by the FT’s John Burn-Murdoch: “Breaking news is the most masturbatory thing journalists do. The reader couldn’t give a flying fuck who broke it.”

A bit of context, here: I was giving a talk about wonk journalism at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, and in the Q&A I was asked about whether there was a problem with the fact that explanatory journalism doesn’t break news. In particular, I was asked about this quote, from James Ball, at the Guardian, writing about Vox and FiveThirtyEight:

Neither site truly aims to break news on the areas they cover, and therein lies a problem: are readers meant to visit their favorite “regular” news sites, then hop by and see if the newcomers have anything to add (or debunk)? Neither FiveThirtyEight nor Vox has offered quite enough (yet) on any of their specialities to become the first stop.

This, I think, is doubly silly. For one thing, both Vox and FiveThirtyEight are brand new: give them a little bit of time to start getting the breadth and depth they aspire to!

But more to the point, readers don’t care who broke the news: only journalists care about that. If I report something and then you report the same thing five minutes later, then by the laws of the journalistic honor code, you’re supposed to credit me in your story.

There’s one exception to this rule: at newswires, it theoretically matters who gets news first, because news can move markets. (In practice, however, even newswire subscribers aren’t generally fast enough to be able to trade on news before the markets have moved, so it doesn’t really make a huge amount of difference whether one wire gets the news a fraction of a second before the other guy.)

Outside newswires, on the other hand, chasing after scoops is silly — especially in the 99% of cases where the news is certain to come out soon enough anyway. Many highly-respected newscasts and magazines rarely or never break news; conversely, many low-quality, high-velocity websites are constantly churning out microscoops of zero importance. It seems self-evident to me that all news organizations should decide whether or not to publish information based on the inherent quality of the content in question, and the degree to which that information serves the publication’s readers. Instead, far too many news organizations make their publication decisions based on what other news organizations have already published.

Journalists, of course, spend a huge amount of time looking at their rivals’ content. And in their solipsistic way, they generally assume that if they’ve seen a certain story elsewhere, then their readers will have seen that story too. Every journalist in America can tell you about a project they were working on which was spiked when their editor saw something vaguely similar elsewhere — even when the overlap between the two publications’ readerships was roughly zero.

All of which is to say that when journalists start caring about scoops and exclusives, that’s a clear sign that they’re publishing mainly for the benefit of other journalists, rather than for their readers. Take the news, for instance, that I was joining Fusion. That news was published in the New York Times — both online and in print. The story, by Ravi Somaiya, was a great one. But because of scoop culture, it only appeared in the NYT because it appeared first in the NYT: Fusion gave Ravi the exclusive. My own story appeared a few minutes later, which is fine; if it had appeared a few minutes earlier, the NYT would probably have refused to publish anything on the subject at all. Even though the only people who care about such things are a handful of media navel-gazers on Twitter, none of whom read the NYT in print.

The argument for caring about such things is that news dissemination has become increasingly fragmented and social: if you have the news first, then your story gets a headstart on Twitter and Facebook, which is how more and more people are getting their news. But frankly while a headstart is nice, it should never make the difference between publishing and not publishing. Readers come first, and all decent publications have their own readership: they shouldn’t be so meek as to assume that their readers will have invariably found the same news elsewhere, just because someone else’s version arrived a little earlier.

James Ball, like most journalists, assumes that news consumers go to news websites in order to find out what is new, what is breaking. But that’s not true. They go to understand the world, broadly. If Vox and FiveThirtyEight help their readers to understand the world, then they will have done their job. No site is exhaustive, and no site will be better at providing all the news that’s happening in the world, on a real-time basis, than the wires and their clients. If you want to succeed online, you need to find a niche, something you do better than anybody else. And it seems to me that explaining and contextualizing the news is a very high calling, even if you can’t explain and contextualize everything.

Of course, explanatory journalism is dependent upon somebody, somewhere, breaking the news in the first place; in my talk I used the word “parasitical”. You can’t have explanation and context without someone on the ground finding and reporting the facts which can then be explained and contextualized.

What’s more, in many cases the person on the ground, who sees the facts in their real-world context, is often the very best person to be doing the contextualizing. That’s why Ezra Klein, for one, is giving his staff beats and is telling them to go out and report news: talking to sources and spending a lot of time in a certain world is pretty much the best way to get the deep understanding of a topic that is necessary to be able to produce a first-rate explainer.

But reporting news, and cultivating sources, is a different thing from breaking news — from being the person who reports the news five minutes or five seconds faster than the other guy. And if you’re not focused on scooping the competition on something incremental, then you’re going to have more bandwidth available for being able to talk to your sources about the big picture, where the real value is.

So let’s try to move away from scoop culture, and away from journalism-for-journalists. Instead, let’s serve our readers. The real readers. The ones who aren’t on Twitter.

Posted in Uncategorized

34 Comments

Taxing future income to pay for college

How to pay for the seemingly inexorable rise in the cost of college tuition? One idea seems to be having something of a heyday right now: since college graduates earn more money, why not levy a tax on them which will pay for the cost of their education? After all, that’s what Australia has done for years, with reasonable success.

The Australian system is a loan: you essentially borrow the cost of tuition, and then repay it, with interest, through your income tax payments. Once you’ve repaid the loan, no more tax is due. The alternative is some kind of straight graduate tax, as proposed in the UK, Oregon, and, now, by Neel Kashkari in California. Although Kashkari’s proposal doesn’t go into any detail, he does say that he wants to offer “four-year college students majoring in a STEM field free tuition in exchange for a small interest in their future earnings”.

Kashkari is restricting his proposal to STEM students (those in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), he says, “to address the potential adverse selection problem”: he doesn’t want a bunch of lazy arts students taking advantage of free tuition and paying back almost nothing from their negligible future salaries. Still, Kashkari’s proposal would be voluntary, so any engineer likely to have substantial earnings after college would rationally avoid the scheme. Instead, it would make much more sense for, say, a botanist planning on spending her career in the field, getting by on grants, post-doc stipends, and the like. Adverse selection works within disciplines just as much as it works across them.

In principle, I’m OK with the idea of graduates paying a slightly higher tax rate than non-graduates. Graduates are in many different ways the “better half” of society: richer, healthier, and generally the people who have got the most out of society, rather than those who have been failed by it. As such, it’s reasonable to ask them to share some of their good fortune with society more generally. But if we are going to have a graduate tax, it should be universal, and it should — like all taxes — be compulsory. The very idea of a voluntary tax is a bit silly, and, as Kashkari says, opens itself up to all manner of adverse-selection problems.

A graduate tax would not be a particularly effective way to tackle problems with education costs. If anything, it would only enable those costs to rise even higher. In general, the cost of college rises to the point at which the pips squeak: universities are becoming increasingly adept at charging just about everybody the absolute maximum they can pay. (This explains why rack-rate tuition charges are going stratospheric: the rich can and will pay through the nose for their education, while everybody else gets a “discount” which is carefully calibrated to bring the cost of tuition down barely into the realm of affordability.) If colleges suddenly found themselves with access to a new stream of income from a graduate tax, they would surely just start raising their tuition rates so that students would still have to take out loans to go to college — even after the government had paid the college from the new funds. Even if tuition were paid for in full, students would still need to find a way to pay for textbooks, room and board, transportation, and other costs. Already, tuition and fees amount to only about 40% of the costs of attending a state college; that percentage could easily fall further.

On top of that, a graduate surtax — even if it was limited to a certain number of years after graduation — would almost certainly end up costing most students more money, over the long term, than current tuition does.

A voluntary tax, however, would take all of these problems and severely exacerbate them — it would enable colleges to charge poor people much more than they currently can, and it would force a massive cost onto anybody unable to pay tuition up-front. Essentially, it would be a highly regressive tax — one paid only by the poor and never by the rich. (Think about it this way: if you could reduce your lifetime tax rate by two or three percentage points, at age 18, for an up-front cost of $50,000, or even $100,000, would you do so? You might well, if you were rich. That’s essentially the deal being offered here, only instead of paying to reduce your tax rate, you’re paying to avoid raising it.)

One version of the voluntary tax is a bit more interesting — the fully private version. The most advanced version of this deal is offered by Upstart: once you have a decent degree, you can then monetize it immediately, by pledging some percentage of your future income in return for an up-front payment. I’ve been skeptical of the Upfront model in the past, but I like it more now, partly because the term has come down from 10 years to 5 years. If this is a private tax, it’s one which doesn’t last much longer than college itself. What’s more, Upstart now offers all students a choice: you can either go down the income-share route, or else you can take out a more traditional loan, with a fixed interest rate.

In both cases, the underwriting process is the same, and operates on an individual, case-by-case basis, rather than broadly, in the manner of a government-levied tax.

There are problems with private taxes, of course. For one thing, unlike public taxes, they’re not tax-deductible: you still have to pay state and federal income tax on your gross income, even though some percentage of that gross income is going to flow straight out to Upstart. And that’s not the end of your tax liability. Upstart sells itself as offering downside protection: if you end up earning very little, you don’t need to pay back the full amount you were given up front. But you are very likely to need to pay income tax on it: the Upstart agreement positively shouts that “ANY SHORTFALL BETWEEN THE FUNDING AMOUNT YOU RECEIVED AND YOUR TOTAL PAYMENTS WILL BE REPORTED BY US AS INCOME TO YOU”. In other words, if you don’t pay back more than you were funded for, you’re going to end up paying income tax on money you were given at least five years ago. Which could be unpleasant.

You’re also likely to pay a substantial sum for that downside protection. Upstart reckons that investors in its platform are going to realize pretty healthy annualized returns, across a diversified base of students — significantly higher than typical interest rates on student loans. Which means that the typical student taking advantage of Upstart’s offer will end up paying more than they would if they’d just stuck to traditional loans: in order to think that you’re getting a bargain, you have to believe that you’re going to be below-average in terms of future salary. Still, there can be good reasons to take the offer all the same. For instance, if you spend a couple of years on some labor of love which pays little or nothing, Upstart will simply defer your obligation, while a student-loan lender will not be nearly as forgiving. (The deferment helps the investor too, of course, who would rather wait for you to start earning real money, and thereby get a higher net return on her investment.)

The fact is, however, that paying for college, either before or after you graduate, by paying a fixed percentage of your future income — well, it’s always going to be a niche thing. As far as the mainstream questions about paying for college are concerned, the CFPB has an excellent guide to the traditional choices. Which should exhaust the possibilities for 99% of students.

The fact that Upstart has launched a loan product is telling: it’s a lot easier to sell debt, rather than equity, to institutional investors, who look at Upstart more for its underwriting technology than as a way of trying to disrupt the way we pay for education. (Upstart reckons that it has a comparative advantage in the loans-to-graduates space: it has a pretty good idea of how much they’re likely to be earning, while most lenders, looking at a blank credit report, will refuse to lend at any rate.)

That’s why Marco Rubio’s proposed bill is very likely to go nowhere. It’s a very aggressive piece of legislation: it allows these contracts to run up to a full 30 years, for instance; it pre-empts the rights of any state to regulate such contracts; and it makes all payments under such contracts “not includable” as a part of your gross income for tax purposes. Basically, Rubio seems to want to be able to privatize the ability to tax individuals for decades at a time, and turn what is currently a clear prerogative of the state into a simple contractual matter between citizens and corporations.

Even putting Rubio’s craziness to one side, however, the idea of a surtax on graduates — even if it’s implemented by the state — is hard to implement, and raises various other problems to boot. For instance: what happens with college dropouts? Do they have to pay the surtax for the years they went to college, even if they’re statistically worse off than high-school graduates? In general, do we really want to tax the one thing that pretty much everybody agrees we need more of?

More broadly still, there are always ethical problems associated with the idea of buying and selling human beings — or even small percentage shares of them. (That’s one reason, I’m sure, why Upstart will let you buy a small share of a graduate, but won’t let you sell that share to anybody else.) The dreadful Fantex shares are up and running now, but I still hope and expect that Fantex will fail. Upstart I think has a brighter future — but probably more in loans than in income-share agreements. And as for state-levied graduate taxes, be they in Oregon, California, or anywhere else, I think we’re still a very long way from them actually being implemented. Especially given the broad opposition they’ve already managed to elicit.

Cooper Union’s response

Here is the response I received from Jolene Travis, Assistant Director of Public Affairs, Media Relations at Cooper Union, after she read my post.

Dear Felix,

After reading “Occupy Cooper Union” (12/5), I writing to ask for a correction to factual errors cited in your article. I have enumerated the points below and, if you have any questions or would like clarification, I would be available to speak with you directly, as I often do with other members of the press such as Brian Boucher.

Best,

Jolene

1) He has released little more in the way of financial information than any of his predecessor

President Bharucha and Vice President of Finance T. C. Westcott have met with students, faculty, alumni and staff over the past year to conduct approximately 80 informational and financial meetings. The meetings are ongoing and open to members of the Cooper Union community mentioned in the previous sentence. Additionally, details about the planning process and financials are also available here: (letters from the President) http://cooper.edu/about/president-bharucha/archived-messages, (audited financial statements) http://cooper.edu/about/financial-statements and (financial FAQs) http://cooper.edu/about/finance-and-administration/financial-faq.

2) A group calling itself Students for A Free Cooper Union has occupied the top floor of the iconic Foundation Building

11 students of the group “Students for A Free Cooper Union” have locked themselves in the 8th floor of the Foundation Building.

3)The Revenue Task Force, they were tasked with finding{revenues which} could not come from other obvious places, like the Board, alumni, or the sale of assets

The relevant paragraph of the Revenue Task Force report reads as follows:

“It should be noted that such areas as minimum trustee contributions, alumni and donor development, and sale of assets were outside the Revenue Task Force’s charge.

http://cooper.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/assets/site/files/RTF-FINAL-REPORT.pdf

4) And so the report comes to the conclusion …that new graduates programs, some of which would charge more than $30,000 per year.

The Deans and faculty for the degree granting three schools will be presenting plans for graduate and other programs (some of the proposed graduate programs could charge in access of $30K) to the Board of Trustees, which will then be reviewed and a final decision is slated for early 2013. http://cooper.edu/about/news/update-president-bharucha-framework-action

5) Cooper might move to a system where a large part of the budget would come from grad students

The evaluation of the plans by the three schools is an ongoing process and the budget is comprised of many facets including, development efforts at the City, state and federal levels along with alumni, foundations and individual members of the philanthropic community

6) Charging for some students would violate Cooper’s mission, which says that it “awards full scholarships to all enrolled students.”

With the financial realities Cooper Union faces, the Board of Trustees has the authority to create programs that generate revenues and, therefore, can amend the mission statement.

7) A document leaked on Monday, written by a mysterious “Undergraduate Tuition Committee” somewhere within the engineering school, lays out all the reasons why Cooper should start charging tuition to everyone.

The acting dean of the Albert Nerken School of Engineering has organized committees to identify possible revenue streams through the creation of new programs. An analysis, which included 500 variables, was conducted to see at what level of revenue would be needed in order to maintain the full tuition scholarship for undergraduates. This is an ongoing process and no decision has been made.

8) A year and a half into Bharucha’s tenure, there’s very little reason to believe that he’s the right man for the job –while the current occupation, which was vocally supported at a press conference Tuesday afternoon, seems to provide a pretty strong prima facie case that his university has no faith in him.

Tuesday’s press conference did not reflect the views of the entire student body and faculty. At today’s Board of Trustees meeting, the Board unanimously reaffirmed their confidence in President Jamshed Bharucha’s leadership.

*Also in paragraph 1, where the WSJ was cited as JB’s favorite media outlet it is important to note that The Cooper Union on a regular basis reaches out to a very broad range of local, national and professional media outlets as appropriate to the subject at hand.

Posted in Not economics

3 Comments

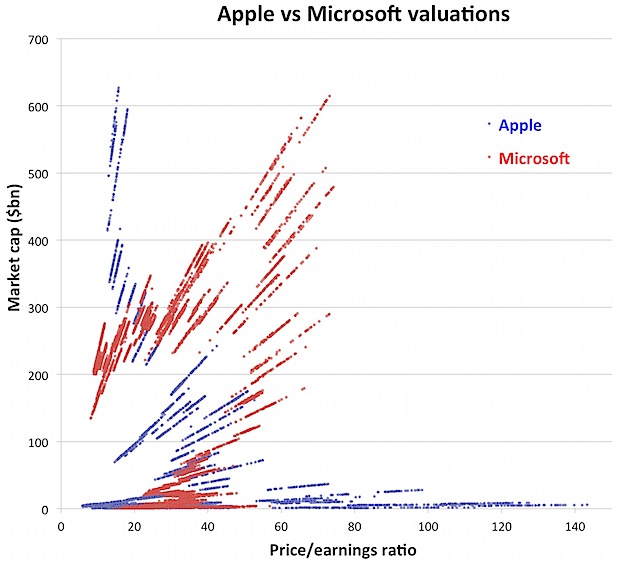

Chart of the day, Apple vs Microsoft edition

Many thanks to Ben Walsh and the Thomson Reuters data team for helping put this chart together. There’s a lot of data here, which isn’t easy to obtain: some 15,000 datapoints in all, going back as far as 1983.

The chart was inspired by this post by Nick Wingfield — the point at which Apple’s market capitalization, in nominal terms, finally exceeded the previous all-time high, which was set by Microsoft in 1999. So we went back and took the closing share price of AAPL and MSFT for every day since they went public, and plotted the market cap against the p/e ratio every day. Apple’s closing prices are in blue; Microsoft’s are in red.

The first thing to notice is the huge difference in p/e ratios at the maximum market cap. The highest AAPL point is a market cap of $627 billion, with a p/e ratio of 15.7. The highest MSFT point, by contrast, is a market cap of $615 billion, with a p/e ratio of 73.

Apple too has traded at whopping great multiples in the past — just look at that long tail of blue dots hugging the x-axis. (In fact, for the sake of clarity I truncated that axis a bit, since it goes on a lot further out than that.) But if you bought AAPL stock at a p/e of 373 you’d look pretty smart right now: the shares have gone up almost 100 times since then. Whereas, if you bought MSFT stock at a p/e of 73, you would just have ended up losing a lot of money.

If you stop looking at individual points and start looking just at the general shapes of the charts, there’s a strong positive correlation on the Microsoft datapoints, and a strong negative correlation on the Apple ones. Generally, with Microsoft, the higher the market cap the higher the p/e; whereas with Apple, the higher the market cap the lower the p/e. (Mathematically, the correlation on the Microsoft data +0.22, while the the correlation on the Apple data is -0.10.)

What this says to me is that the market in Apple shares looks a lot more rational than the market in Microsoft shares. Investors will pay huge multiples for Apple shares when the company looks cheap, but not when the company looks expensive. When Apple breaks the half-trillion barrier, that’s despite the fact that its p/e ratio is low; when Microsoft breaks that barrier, it’s because its p/e ratio is high.

So when Wingfield talks about “investor euphoria” surrounding Apple, bear in mind that the euphoria he’s talking about is very different from the kind of euphoria we saw at the height of the dot-com bubble. Apple is indeed worth a truly enormous amount of money. But investors don’t see the kind of scalability in Apple, circa 2012, that they saw in Microsoft circa 1999. Despite the fact that the global market for smartphones today is vastly greater, and growing much faster, than the global market for Windows software was in 1999.

Update: I’ve put the data here for those who want to play around with it themselves.

When private-school tuition is tax-deductible

Scott Asen, a former trustee and head of the development committee at Groton, a posh private school, has a revealing op-ed in the NYT. He explains that at such schools, the tuition fees, high as they are, fall well short of covering the annual costs that the schools incur; the difference is made up by donations and, where it exists, by using the school’s endowment. What’s more, that fact is explicitly communicated to parents. “Virtually every private-school parent has heard about ‘the gap'”, he says, and, as a parent, once you know about it, it’s clear what you should do:

To the extent that any family with the wherewithal is paying less than the full cost of the product it is buying through combined tuition payments and donations, that family is effectively being subsidized by other current and past donors. Not only is this ethically unsupportable, but ultimately, it is also financially unworkable.

Asen proposes that all parents who can afford to do so, or who fail to provide financial disclosures proving that they can’t afford to do so, should be “expected” to “fill the gap” with a donation. “Given the strength of the educational product offered by these prestigious schools,” he writes, “I think that for every affluent family scared off by the new policy, there would be another of equivalent means — with an equally desirable child in tow — willing to pay full cost.”

Many parents are following these guidelines already, thanks to pressure from people like Asen. “It’s sort of understood that if your children attend these schools and you can afford it, you will pay all or some of that shortfall,” one father told Jenny Anderson.

The operative word here is “pay”. These payments are just that: money spent to cover the costs of educating Junior. As Asen’s headline puts it, right now private schools are “not expensive enough” — they should cost more. And while the extra money might be couched as a donation for tax purposes, both the school and the parents understand that if you’re merely “filling the gap”, rather than, say, donating a couple of million dollars towards a new gym, then you’re really just covering the annual cost of your kid’s tuition.

Such expenses are not, and should not be, tax-deductible. What Asen is proposing comes very close to tax fraud: he’s clearly saying that if you’re the kid of parents of means, and your parents refuse to fill the gap, then you would no longer be welcome at school. For rich parents, this is to all intents and purposes a tuition hike. But it’s sweetened, a little bit, with the fact that the hike is fully tax-deductible.

Tuition hikes at private schools have never been tax-deductible in the past, and they shouldn’t be tax-deductible now. If Asen wants to suggest that private schools should just raise their rack rate to an amount that covers the cost of tuition, and then use some of the extra revenue to help defray the cost for children of parents outside the 1%, then that I think would be perfectly reasonable.

There’s a curious tension among the kinds of people who send their kids to private school: on the one hand, they do so in large part precisely because these are the schools attended by the kids of the money-is-no-object types. But on the other hand, they like to think that the schools are attended by a diverse group of the best and the brightest, rather than just the richest. And so they support the idea that some carefully hand-picked kids from less flush families should also be able to attend. If Asen’s proposal was a simple tuition hike with some kind of concomitant increase in financial aid, then, it would just represent an institutionalization, within the tuition structure, of diversity principles which are already espoused by most private schools.

But Asen doesn’t go that far. Instead, he takes to its logical conclusion the woeful trend of the transactionalization of philanthropy: the idea that it is entirely normal and expected for every tax-deductible philanthropic donation to be tied to the charity in question providing something of value in return. It starts with the tote bags given out during public-radio pledge drives, and ends with the very institution changing its own name to yours: the Peter G Peterson Institute for International Economics, the Booth School of Business.

In general, where something of real value is given back, only the difference is tax-deductible. If I buy $350 tickets to a charity dinner, and the dinner costs $150, then only $200 can be written off against taxes. And if I get a discounted ticket to the dinner, paying only $100, then none of my payment is tax-deductible. That’s essentially the situation that private-school parents are in right now: they’re buying discounted tickets to an extremely expensive education. If they end up forking over a bit more, but still less than the education costs, then nothing changes, and the extra amount they pay should still come out of post-tax income.

All of which helps to explain why private schools charge less for tuition then they spend on providing it. Within days of their kid being accepted at a private school, parents are informed about the famous gap, and pressured to fill that gap with a donation. In the school’s ideal world, all parents would then fill that gap to the limit of their ability to pay — and rich parents would give even more. The parents, of course, will always be happier paying low tuition and topping it up with a tax-deductible donation than they would be simply paying higher tuition.

But donations have to be voluntary, and no matter how good a school is, there are always worthier charities out there. After all, the US already has universal education: the charitable purpose of the private school is just a marginal increase in the quality of some children’s education — complete with deleterious effects on everybody else. (Just imagine how much better Manhattan’s public schools would be, if all of the island’s super-rich had to send their kids to those public schools.) If I have $10,000 to give to charity, it’s really hard to believe that the first best recipient of that money would be some private school, rather than, say, Doctors Without Borders.

So if schools want parents to donate money, they have to offer something extra in return: they have to offer to educate the parents’ kids. That’s why tuition is set below the cost of education: it forces the parents, in aggregate, to donate the difference, for fear that otherwise the kids’ education might suffer. And it also helps to lay the groundwork for deals like the notorious one between Sandy Weill and the 92nd Street Y: Sandy donated $1 million of Citigroup’s money to the school, and his star analyst managed to get his twin daughters into the pre-school there.

That deal was particularly obnoxious, but it’s entirely commonplace for very rich parents to drop very large hints, along with their private-school applications, that if their kids get in, substantial donations will accompany them. Naturally, the schools are predisposed to accept precisely those kids. Given that those donations appear if and only if the kids attend the school in question, there’s a case to be made that all such donations, even if they’re much larger than the gap, are in effect payment for tuition, and should not be tax-deductible.

I’m no fan of the tax-deductibility of charitable donations in the first place — it’s an enormous tax expenditure which results in a relatively modest amount of extra charitable giving. (Ed Dolan has a good two–part overview of why the deduction is a bad idea.) But let’s put that debate to one side for the time being, and make the reasonable assumption that the deduction is here to stay. Let’s also make the equally reasonable assumption that Asen’s proposal won’t get adopted by any private schools, for the very good reason that it would never pass muster with the IRS.

Then what we’re left with is an admirably clever op-ed by Asen, which sends one message while purporting to say something else entirely. His op-ed is nominally directed at schools, saying that they should change their tuition structure. But the real target is not schools but parents. He’s telling them that private-school cost inflation is enormous, and that they have an ethical obligation to fill the gap, every year, if they can possibly afford to do so. Stripped down, the message is this: “give more, or you won’t like the consequences”.

Development officers sharing Asen’s op-ed with parents will surely be very quick to point out that you can’t make tuition a tax-deductible expense, and that if schools were going to raise their tuition rates, none of that raise would be tax-deductible. As a result, they’ll say, it’s much better for all concerned if the present situation stays in place, and parents top up their tuition fees with tax-deductible donations.

Asen’s op-ed, then, is at heart a fundraising drive aimed at the status quo, rather than a real attempt to change that status quo. As you would expect from someone who spent many years raising funds for a private school. I wonder if the NYT realized that, when they printed it.

Man U’s weird share price

I have absolutely no idea what on earth might be going on with the MANU stock price. But it’s definitely another datapoint supporting the thesis that IPOs are weird things best avoided. (See also Facebook, of course, and Groupon, and just about any of the other buzzy companies to have gone public of late.)

The chart above — there’s a bigger version here — shows the Man U’s share price since the IPO last week. And the weirdest bit of all is actually the first day, when seemingly nothing happened: the stock never moved more than 2% from its IPO price.

But as Matt Levine noted that afternoon, after the market closed, the underwriters were clearly supporting the stock at the IPO price of $14, and the volumes being transacted at that level were truly enormous: much bigger than the official greenshoe. Either someone was accumulating an absolutely massive chunk of stock in the open market, or else the underwriters sold an insane quantity of shares at the IPO — almost double the final free float of 16.67 million shares. Neither theory was particularly plausible on its face.

Clearly without support, the Man U share price would have dropped below $14. But then something very weird happened when the shares reopened on Monday August 13: after half an hour at $14 per share, they suddenly spiked; at one point that morning they were more than $15 per share. Was Man U stock going up, rather than down? Were the people who bought on the opening day being vindicated? Or was this some weird kind of short squeeze?

Subsequent price action didn’t help clear anything up. On Day 3, Tuesday, someone was clearly providing support at $14.16 per share. And on Day 4, Wednesday, we had a mini-repeat of what happened on Monday: the stock suddenly spiked upwards for no good reason from its former support level.

By the end of the day, however, and on Thursday afternoon, we were back down to the $14 IPO price — and again someone was supporting at that level — until, at 11:10am, they weren’t. At long last, the drop that everybody had expected for Monday morning had finally arrived, and for the time being the stock is floating around somewhere near the $13.40 level.

I could try to construct a narrative which might explain all this, but I’d frankly just be making things up. The one thing that I can be pretty sure of is that we’re not seeing price discovery here: this isn’t the natural forces of supply and demand determining how much Man U shares are worth. What it is, however, I have no idea at all.

Update: This might explain a lot.

$5,000-an-hour lawyers

David Lat has the numbers today on how much the top partners at Dewey & Leboeuf were making. At the top of the list are Berge Setrakian and Ralph Ferrara, both of whom made around $12.5 million in 2011.

As far as I know, the top recorded rate that any lawyer bills out at is Ted Olson’s $1,800. And obviously the amount of money that law-firm partners make is not the same as the amount they bill out at: they’re not just workers but they’re also part owners of their law firms, and share in the whole firm’s profits. But it’s still an interesting exercise to take annual income and divide it by billable hours to see what top law firm partners can make per billable hour.

And here’s the glorious thing: even if you assume that Setrakian and Ferrara bill 2,500 hours per year, that $12.5 million works out at an eye-popping $5,000 per billable hour.

Of course, at these levels, you’re not (just) being paid for the direct work you do for clients: what you’re really being paid for is bringing new clients into the firm and getting the firm revenue streams which can reach hundreds of millions of dollars. But there’s still a reason why those clients will follow you to the firm, and that reason is that the clients will expect you to do real work for them.

Which helps to clarify exactly where the value lies, in law firms. Junior associates get paid less money than they bill out at; partners get paid more money than they bill out at. At the same time, it’s very unlikely that the clients really think they’re getting $400 an hour in value from a relatively junior lawyer poring over boilerplate at 2am.

In other words, differences in billable rates are basically an accounting fiction, which is used to come up with a calculable final figure to be presented as the bill, but which do not actually reflect the difference in value between various strata of lawyers. In order to do that, you’d be better off dividing annual income by, say, 2,500.

If you’re earning $250,000 a year, then that means you’re earning $100 per billable hour, if you work really hard. And if you earn $12.5 million, that works out at $5,000 per hour.

All of which is to say that Ted Olson’s $1,800 is low. And I suspect that if you multiply the number of hours he bills per year by $1,800, you’ll end up at a fraction of the amount he’s actually paid.

Posted in economics

8 Comments

More data on 401(k) loans

In my post about Bob Litan and his estimates of 401(k) loan defaults, one of the key bits of weirdness was the way in which he decided that the total number of 401(k) loans outstanding had doubled since 2009. The official Private Pension Plan Bulletin says that 401(k) loans totaled $51.7 million in 2009, but Litan, in his paper on the subject, puts total loans at $104 billion, saying that the 2009 numbers are “outdated”.

Now, Guan Yang points me to some new data from the Labor Department, disclosed in response to a FOIA request. The data is raw, of course, and hard to parse; the loans appear in both Schedule H and Schedule I, for instance. But my colleague Jessica Toonkel asked the chaps at Brightscope to take a look, and this is what they found:

| Year | Schedule H loans, $ | Schedule I loans, $ | Total loans, $ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 40,920,193,973 | 1,845,546,770 | 42,765,740,743 |

| 2007 | 43,333,714,360 | 1,815,617,332 | 45,149,331,692 |

| 2008 | 48,736,802,777 | 1,369,538,610 | 50,106,341,387 |

| 2009 | 48,332,673,154 | 1,552,443,970 | 49,885,117,124 |

| 2010 | 52,654,869,898 | 1,428,015,075 | 54,082,884,973 |

| 2011 | 709,094 | 22,082,885 | 22,791,979 |

This is raw data from Form 5500, the form that pension plans have to file with the government. Most 5500s for 2011 haven’t been filed yet, so the numbers for 2011 are only extremely partial and are pretty much useless. But what we can see is that there was no big rise in total loans between 2009 and 2010, as Litan and his co-author, Hal Singer, imply. If total loans did go up, they only went up by a single-digit percentage: there’s no way they more than doubled.

To double-check with the data that we do have for 2011, the Brightscope people also looked at total 401(k) loans as a percentage of total defined-contribution assets. That was 1.76% in 2008, 1.73% in 2009, and 1.75% in 2010: pretty constant. In 2011, as I say, we only have very partial data so far. But from the data we do have, covering just under $2 trillion in assets, that ratio is just 1.17%: it’s low, not high. As more data come in, that ratio will surely rise. But again, there’s no reason at all to believe that the number of 401(k) loans rose sharply in 2011.

In any case, these numbers alone should be enough to persuade anybody that the Litan-Singer estimate of as much as $37 billion in annual 401(k) loan defaults is just silly: $37 billion is more than 60% of the total number of 401(k) loans outstanding in 2010. And most people, of course, do pay back those loans.

Posted in economics

4 Comments